THE VITNAM ERA is often remembered more for its anti-war sentiment and politics of social change than for the actual conflict that spurred this counterculture. We’ve been content to relegate this less-than-ideal part of our history to just that—history. And for those Marylanders who served in Vietnam—the soldiers, nurses, aid workers—being forgotten was, at least for a while, preferable to the vitriol of an anti-Vietnam populace.

But now, their stories are finally being told. A new documentary from Maryland Public Television, “Maryland Vietnam War Stories,” features nearly 100 local veterans talking about their experiences. It will premiere across three nights, May 24-26, and likely air on PBS stations across the country in June.

The documentary even includes, impressively, a handful of women—an underrepresented group in an already underrepresented group.

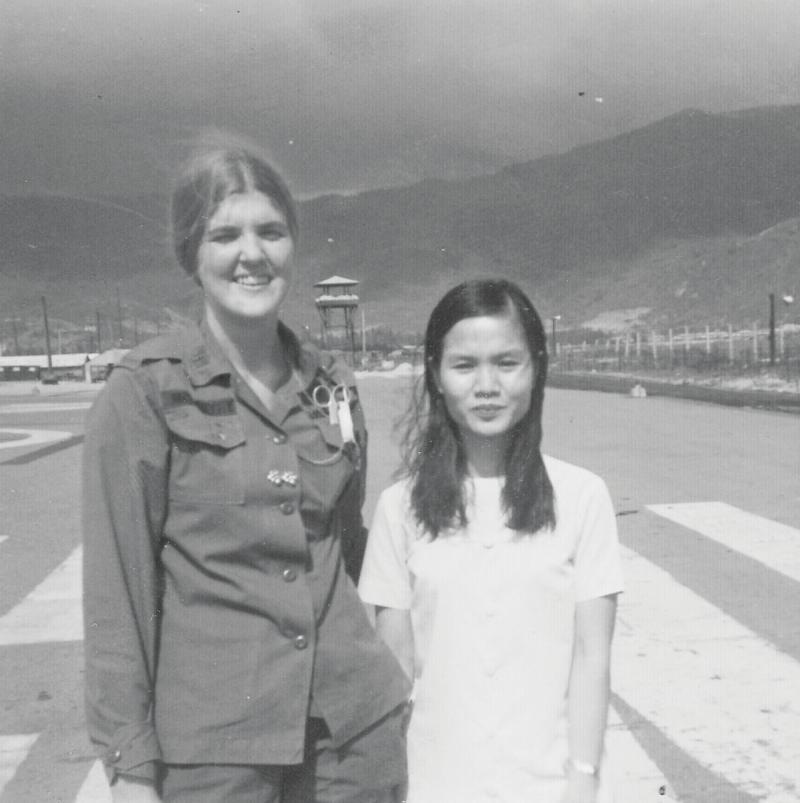

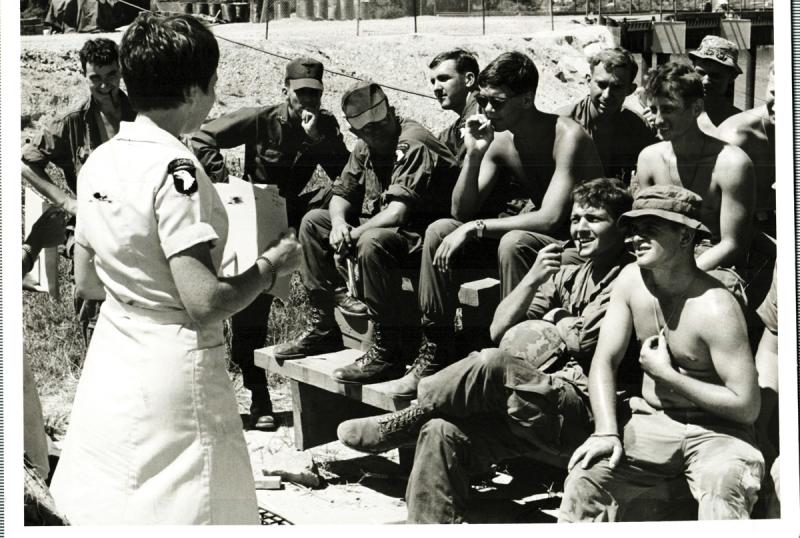

At that time, women could not serve in the military except as nurses, or go overseas in another capacity, like with the Red Cross or other aid organizations.

Jane McCarthy, now 67 and living in Olney, was one of the former, an Army nurse with the 95th Evacuation Hospital in Da Nang, Vietnam. McCarthy was a small-town girl from Cohasset, Mass., about 30 miles outside Boston. In the late 1960s, while she was attending Massachusetts General Hospital School of Nursing, the young men she grew up with in her town of fewer than 7,000 were being drafted.

“I was coming home every six months for a funeral of one of my friends, the guys who had to go,” she says. By the third funeral (of Allen Keating—she still remembers his name—who was killed in Vietnam at the age of 21), she stood at his grave and said, “I have to do something.”

She wasn’t in favor of the war—“No one was,” she says—but if these men could sacrifice, so could she. She joined up, with one year still left at nursing school. After finishing, her next few months were a whirlwind: she graduated in August, took her Registered Nurse exam in September and reported for basic training by October.

After the six weeks of basic training in Texas, she was stationed at Walter Reed Medical Center for 10 months. Then, at 22, with that minimal experience under her belt, she was shipped out to Vietnam.

“It was pretty scary,” she says. “I remember landing in Saigon and there were flares going up; I thought they were bombs! I mean, what did I know? I knew nothing—absolutely nothing —about war.”

She worked as a triage nurse, separating patients based on severity of injuries and what medical treatments were needed. Sometimes, all she could do was hold a soldier’s hand as he breathed his last.

She came home radicalized, joining Vietnam Veterans Against the War in college and going to protests. Looking back, she realizes now that her difficulty adjusting back to civilian life and subsequent depression at the time were symptoms of undiagnosed PTSD.

For other women, joining up was a chance to escape the “Leave-It-to-Beaver” confines of their gender and fulfill their desire to see the world, a trait not much admired in women at the time. Bobbi Hovis, a 90-year-old from Annapolis, who spent her entire career as a Navy nurse, grasped at the opportunity with both hands—and has the stories to prove it.

By the time the Vietnam War began, Hovis was no stranger to danger, war or nursing. In high school during World War II, she was inspired by her uncles in the Navy to set her sights on becoming a Navy flight nurse.

So, she joined up, specialized in aviation medicine—a prerequisite to become a Navy flight nurse—and obtained her pilot’s license on her own and flew with medical air evacuations during the Korean War.

“I really fell in love with Southeast Asia,” she says. “I decided I just had to get back there somehow.”

By 1963, Hovis, raring for her next adventure, was among the first nurses to volunteer to go to Vietnam. In fact, she helped establish the Navy Station Hospital in Saigon.

If anyone was made for the very difficult work of being a nurse in a war zone, it’s Hovis. Her irrepressible sense of adventure and good humor served her well, despite the often grim surroundings.

“It’s always hard to see a kid die with your hand on his pulse,” she says. “…But you can’t let it get to you. You cope with it.”

Even as a nurse, Hovis had her share of close calls. Because she was also a pilot, she would sometimes get orders to help out the air medevac teams when they were overwhelmed. On one particularly memorable trip back from the Philippines, Viet Cong soldiers had set up a machine gun in the jungle near her landing strip, shooting at any planes attempting to land.

She had to come in “high and hot”—pilot-speak for a pretty rough landing. She dropped so quickly, her earplugs popped out from the pressure and blew out her eardrum. When she climbed out of the plane, the tail was riddled with bullet holes.

Hovis was (and still is) unfazed. “Oh, I have a lot of stories like that,” she says.

Her other near-miss came, of all places, at the hospital. The Viet Cong had stormed into Saigon and, never one to miss a chance for derring-do, Hovis stepped out onto the fifth floor balcony to get a closer look. Just as she turned and made eye contact with a Viet Cong soldier across the street, he fired. The bullet hit the front of the balcony and ricocheted off the ceiling, only to land at her feet. A few inches higher and it would have embedded in her chest.

She still has that bullet.

“That was probably my closest call,” she says, as if she has to think about it.

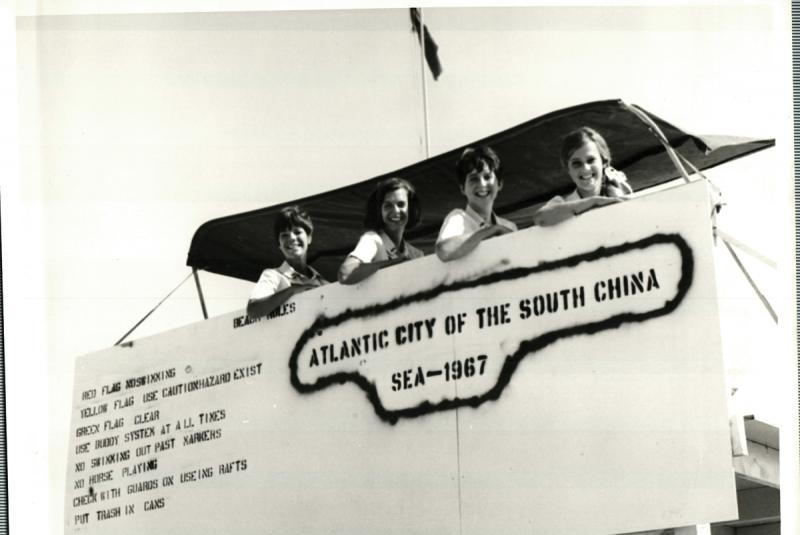

Not all women who went to Vietnam were nurses, however. A few, like Linda Sullivan-Schulte, went over with aid organizations. For Sullivan-Schulte, it was the Red Cross. She was accepted to be part of the Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas program. (Going into a heavily male warzone with a group name like that, well, the inappropriate jokes just write themselves.)

They were called the “Donut Dollies,” a holdover name from World War II. Their job was to improve soldier morale (mind out of the gutter!), which usually involved them traveling to various bases, performing and just being a joyful presence in a harsh setting.

“It was an amazing experience because it worked,” Sullivan-Schulte says.

She had been anti-war, but, coming home, she found herself passionately pro-soldier instead. She still wanted the war to end, but for the sake of the soldiers and their desire to come home.

All the vets agree: A Maryland-centric documentary like this is overdue. They’re enthusiastic to see it air. But, as Sullivan-Schulte says, there’s one thing even more important.

“I’m excited to see this whole group of soldiers [finally] being recognized.”

LESSONS LEARNED FROM VIETNAM

The Vietnam War wasn’t just a military failure—it proved a great disservice to the returning veterans. Faced with a society that blamed them for the war, many veterans had trouble readjusting to civilian life. They also faced a lack of resources when it came to dealing with the psychological trauma of war.

>>A 1980s survey of Vietnam veterans conducted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimated that nearly one-third (31 percent) had suffered from PTSD at one point in their lives. That’s especially steep when compared to veterans from conflicts since then: 11 percent for veterans of Afghanistan and 20 percent for Iraq.

>>We learned at least this one lesson, it seems, from Vietnam: Whatever our view on the war, those serving deserve our respect and our resources. In the years since Vietnam, we’ve engaged in conflicts around the world, most notably in the Middle East. But even amid the rising tide against our presence in places like Iraq and Afghanistan, the “Support Our Troops” mantra has not been forgotten.

>>Vietnam is also remembered for the difficulty the U.S. Armed Forces had combating the guerilla-style attacks of the Viet Cong. Modern conflicts have continued this vicious trend, lacking front lines or traditional combat.

>>As the style of war changed, so, too, did the military. During Vietnam, women were allowed to serve, but mostly as nurses or administrative personnel. They made up less than 1 percent of those stationed in Vietnam.

>>Slowly, more and more military jobs opened up to women, although it could be slow going—women couldn’t enter the service academies until 1976 and weren’t selected for flight school until the ‘80s. But, eventually, only certain combat and special-forces positions remained closed to them. Now, even that has changed.

>>U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter has ordered that all gender-based restrictions on military service be lifted in 2016.

>>In 2015, women made up about 15 percent of active military personnel, according to the Department of Defense.

This article appears in the May/June 2016 issue of STYLE.